Origins of present-day Nuristani peoples remain a mystery, although some of their ancestors might have been soldiers of Alexander the Great. Physically, the people appear like Europeans; blond or red hair and blue or green eyes are more frequent than in other Afghan people. Alexander's records from 327 BC mention his expedition there and his armies' defeat by fierce-fighting mountain tribes in the Kunar River area, where they sustained considerable losses. Not long after when Alexander died, his army disbanded. There is no documentation regarding whether remnants of his forces remained in the area. It is interesting to note, however, that Nuristani games echo those of Greece—javelin throw, shot put and a discus throw using an 8" round, polished stone. Even today, they hold village competitions and award trophies, culminating in an annual tournament.

Nuristani people groups are unique amid others living in Afghanistan—so unique we cannot view them through a single lens. Their only common threads may be religion, ethnicity and remnants of customs pre-dating their collective conversion to Islam little over 100 years ago.

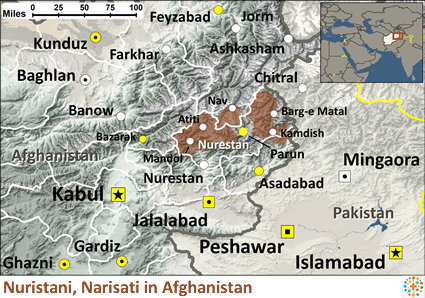

Ethnically, the Nuristani people cluster embraces eight groups – the Ashkuni-Wamayi, Bashgali-Kati, Grangali, Kamviri, Malakhel, Waigeli, Prasuni, and Tregami. Linguistically, however, two of these clans speak languages unrelated to the Nuristani family of Indo-Iranian languages. Often, a language spoken in one valley is unintelligible to a near neighbor in another. None of their languages are in written form and their literacy rate in other languages is very low. Oral traditions testify to longstanding interaction between groups through the centuries despite language barriers. Geographically, as early inhabitants of the Nuristani region in northeast Afghanistan, most still live there. Focus here is on the seven groups still living in the mountains of Nuristan.

Renowned as an area of astonishing beauty that shares its eastern border with Pakistan, Nuristan spills down the craggy southern heights of the Hindu Kush Mountains into valleys holding the watersheds of four major rivers. A fairly consistent climate provides sufficient rainfall to sustain lush forestland–in stark contrast to the barrenness of other parts of Afghanistan–and to irrigate crops directly or through a network of canals. They grow wheat and corn in terraced plots because arable land is sparse.

Oral accounts from tribes dating to a thousand years ago show they lived northeast of the merging point of the Kabul and Kunar Rivers, having moved westward to escape encroaching Muslims, whom they viewed as belligerents intent on forcing Islam upon them.

Their beliefs had roots in an older form of Hinduism that featured a supreme creator and lesser gods who distinguished between impure humans and pure gods. One's destiny was determined by these gods, although they could make appeals through animal sacrifice and prayer. Large feasts assured the host purity and favorable community status. They offered honor to the gods through a shaman and local animistic rites became intermingled. It supplanted this religion after some 800 years of resistance when, in 1895, the Nuristani clans were out-fought by Amir Adur Raham Khan's forces and forced at sword-point to convert to Islam. Previously, the region had been called Kafiristan by the Muslims – "Land of the Non-Believers" or infidels. Muslims renamed it "Land of the Enlightened"—Nuristan.

Nuristani men have a dashing reputation among other Afghans as possessing unruly natures, so it seems natural they were the first to mount an undefeated revolt against the Russian invasion in 1978. Although there was a decade more of war with the communists, it was their actions that inspired the resistance of other Afghan militias that eventually broke the Soviets and drove them out.

Isolation has proved two-edged. It has hindered potentially beneficial development, leaving Nuristan as one of Afghanistan's most impoverished areas. Isolation has helped the people preserve their culture and language.

It is the women's task to perform agricultural chores, often using primitive tools for cultivation. Pastureland for goats and cattle, is tended by the men. When the first settlers found natural resources limited by the rugged terrain, groups fought for land and stole livestock from one another. Left unchecked, if no village mediator was available, retaliation to defend a tribe's possessions led to volatile relations between the clans, even blood feuds that continued for hundreds of years.

Most Nuristani subsist as farmers and herders but in this remote and difficult to access region where steep, narrow paths challenge even mules and transport is mostly on foot, some men work by logging or illicit gem mining enterprises. Some logging is legitimate, some not, but all gem extraction is illegal by government restriction. They transported both beyond the central government's control through Pakistan, funded by outside entrepreneurs who, as the suppliers of the capital and machinery, reap huge profits that are not fairly shared with local laborers. Gems are the region's primary resource. They mine rubies, emeralds, lapis lazuli, and tourmalines of a superior quality known since 5000 BC to silk road traders.

Nuristani villages, ranging from 30 to 300 families, are the core of a patriarchal culture. Influential men, called mediators, are respected for skills in negotiating conflicts to a non-violent end, perhaps with the aid of a local or area council of leading men. Peace beyond an immediate village depends on relationships formed by intermarriage or through friendships with men in other villages who "adopt" one another as brothers. Historically, men were the property owners, with male heirs the inheritors of grazing lands. Now, under Islamic law, women have the right of inheritance but in reality, her brothers or uncles usually control her portion.

Besides division of labor by gender. Landowners are the "upper class," the decision makers. The "lower class" (slaves in earlier times) are the craftsmen—woodworkers, weavers, potters, basket makers, blacksmiths, and carpenters. They put their skilled handiwork to use in every village dwelling.

Cited as reliable and loyal, they are creative too, as attested to by their skilled architecture and craftsmanship. Homes, many perching precariously on mountainsides, differ locally in construction details. They might be built of wood, stone or mud. A common type has a stone foundation, multiple stories, a flat roof supported centrally by substantial wooden columns and no fence—a detail rarely, if ever, omitted in other Afghan villages. A window would face east, another west to allow a view of sunrise and sunset. They put their doors somewhat above ground level. Three spaces are typical—one for family living and two for storing wood and grain.

A stone cooking hearth is at the center of the family's upper room with a hole in the ceiling above to release smoke and admit daylight. Nuristani furniture is distinctive, as some of it is carved and may feature chair backs painted in various colors. Chairs and stools with leather strip seats, together with a wide, short-legged table sit near the hearth. Beds are further away while wooden wall racks hold carved wooden, stone or metal utensils. An unusual feature is an area on the ground floor set apart in a corner for bathing and washing clothes. Goat wool rugs, even a carpet may cover the floors. Stone, copper or clay lanterns and/or torches provide night lighting.

Meals historically symbolize the importance of male and female, because it is customary for both to contribute food to them. Since the crops grown are insufficient, meals are simple. A wife provides bread baked from her grain fields, while the husband contributes cheese, butter or yogurt from his flocks. Herd animals provide occasional meat, but they don't eat poultry because birds, according to a myth, represent dead souls.

Dress varies among Nuristani tribes although some favor black or white clothing. One distinction is true of all Nuristani women—the veil has never been required attire even though they are Sunni Muslims.

Marriage traditions, like preferable age, differ from other Afghan groups. For Nuristani women it is 20; for men, 25. They forbid marriage between first cousins. They require a bride price in cattle, but if the groom cannot pay in full, he may work for the bride's family to satisfy the remainder of his debt.

The birth ritual is decidedly different among Nuristani peoples in that babies are not born at home. Beyond village limits, each community maintains a large building with several rooms where mothers stay a few days before and after giving birth. Despite such care, the maternal death rate is very high. Bestowing a child's name follows interesting traditions as well. After they sacrifice two goats to welcome a male child (one for a girl) they shave the boy's head, and name him for his father or grandfather. Another method is to lay a child at the mother's breast while reciting ancestor's names. The child receives the name mentioned as he first begins to feed. At twelve years, they celebrate a male's maturity with a feast.

Pre-Islamic funeral ceremonies were elaborate, unusual affairs in that during a week of bereavement, slaves carried and danced with a wooden figure cut to the deceased man's height. Relatives provided food to mourners. They buried a warrior's weapons in the coffin with him; a woman's ornaments with her. Also placed in coffins was a pot of symri (crumbled barley bread). A year after a man's death, they erected a wooden statue as a memorial and made sacrifices to honor him at festivals thereafter. Several ancestral figures are on display today in the Kabul Museum.

Holidays and annual feasts held an important place in the clans' social lives. They praised their ancestors and danced to local-style music for entertainment. Sunni Islam and Taliban influence have largely suppressed both cultural expressions. Previously, harvest festivals included group dancing accompanied by tambourines, flutes, large drums, a 6-stringed harp and hand-clapping. They also enjoyed choral singing.

The Narisati people are Sunni Muslims who believe that the supreme God, Allah, spoke through his prophet, Mohammed, and taught humanity how to live a righteous life through the Koran and the Hadith. To live a righteous life, you must utter the Shahada (a statement of faith), pray five times a day facing Mecca, fast from sunup to sundown during the month of Ramadan, give alms to the poor, and make a pilgrimage to Mecca if you have the means. Muslims are prohibited from drinking alcohol, eating pork, gambling, stealing, slandering, and making idols. They gather for corporate prayer on Friday afternoons at a mosque, their place of worship.

The two major holidays for Sunni Muslims are Eid al Fitr, the breaking of the monthly fast and Eid al Adha, the celebration of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his son to Allah.

Sunni religious practices are staid and simple. They believe Allah has pre-determined our fates; they minimize free will.

In most of the Muslim world, people depend on the spirit world for their daily needs since they regard Allah as too distant. Allah may determine their eternal salvation, but the spirits determine how well we live in our daily lives. For that reason, they must appease the spirits. They often use charms and amulets to help them with spiritual forces.

Current needs are many. Communication is difficult – again due to remoteness and topography, even erratic weather. As recently as 2007, reports indicted that health care is virtually non-existent and schools are few in most of Nuristan. The need for roads to bring access for aid and development projects, as well as to bring in food and supplies is urgent. Often it is the Nuristani themselves who impede progress. To blame is an historical distrust of outsiders, a determined independence, in-fighting and even a lingering fear of spiritual consequences.

Developing a nationalistic sense may take decades to achieve, but a remark from a native in 2008 offers promise. "We are facing injustice in Afghanistan but [hopefully] the new generation of Nuristan will ... make it a heaven for tourists, not a haven for terrorists."

Pray for spiritual blindness and bondage to the evil one to be removed so they can understand and respond to Christ, the one who offers them life to the full.

Pray for the Lord to provide for their physical and spiritual needs as a testimony of his power and love.

Pray the Narisati Nuristani people will have a spiritual hunger that will open their hearts to the King of kings.

Pray for an unstoppable movement to Christ among them.

Scripture Prayers for the Nuristani, Narisati in Afghanistan.

| Profile Source: Joshua Project |